Common Song for An Uncommon Film

ON A JUNE EVENING IN 2002, ethnomusicologist Tim Eriksen M.A. ’93 got a call that changed his life.

ON A JUNE EVENING IN 2002, ethnomusicologist Tim Eriksen M.A. ’93 got a call that changed his life.

He and his wife, fellow ethnomusicologist Mirjana (Minja) Lausevic Ph.D. ’98, were living in Minneapolis. She was a professor at the University of Minnesota. He had a solo singing career and was lead singer/guitarist in a folk-punk band. Their son, Luka, was six months old.

On the other end of the line, Sonya Cohen ’88 was explaining that her father, musician and folklorist John Cohen, needed Eriksen’s vocal expertise on a project. He had been hired as a consultant on an upcoming film set in 19th-century America, and he needed to find a singing voice for a character, someone who could sing ballads of that era. “There’s a pretty limited number of us who do that,” acknowledges Eriksen drily.

This, however, is Eriksen’s forte. At Wesleyan he studied and wrote his master’s thesis with composer and Professor of Music Neely Bruce, one of the nation’s leading authorities on early American music.

Later, John Cohen tried to persuade Eriksen to join the project: It was bound to be a success. T-Bone Burnett (O Brother, Where Art Thou) was producing the music. Anthony Minghella (The English Patient) was the screenwriter and director. Hollywood stars Nicole Kidman, Jude Law, and Renée Zellweger were playing the leads. Miramax had the rights to it. The movie was based on an award-winning novel by Charles Frazier. Maybe Eriksen had heard of Cold Mountain?

“I didn’t know who any of these people were, other than John,” says Eriksen, whose tastes run to the esoterically eclectic, rather than the popularly mainstream. “I was skeptical. I thought it was interesting, but I don’t have a lot of enthusiasm for Sony or Disney.” He pauses. Thinking about Luka and their new baby Anja, he admits: “Although I do watch a lot of Disney movies these days.”

“Working with a big corporation wasn’t something I wanted to do—but my wife talked sense into me.”

After a week, he agreed to be the singing voice for Stobrod (actor and fiddler Brendan Gleeson), as well as to advise on a form of old-time singing: Sacred Harp.

Also called “shaped note” music for its system of notation—triangles, circles, and the like—Sacred Harp music took its name from a 19th-century book of religious and patriotic songs in four parts. The “sacred harp,” explains Eriksen, is the human voice. Both he and Bruce are active in fostering this traditional form. But don’t look for it in any performance venue: Those who enjoy it attend daylong sings, punctuated by a pot-luck lunch. The music is strictly participatory. Did the producers understand how strange it would be to bring this to the Hollywood screen? They did. To Eriksen, that was key.

When Burnett shared his plan to hire a choir to sing the Sacred Harp music, Eriksen set him straight. “A choir has a different sound from just regular people singing,” he explains. “To T-Bone, it made sense: if you need people singing in a church, you hire a choir.” But it wouldn’t have been Sacred Harp music.

To illustrate, he organized a sing in Alabama, at the Liberty Baptist Church, and invited the Cold Mountain team. “I still didn’t know who these [Hollywood] people were, and I didn’t know if I could fully trust them,” he admits. “I wanted them to see that these singers were real people and you couldn’t just use their music any way you wanted.” It wasn’t a “thing”; it wasn’t a product. The music belonged to those who had made it and Hollywood would have to respect that.

As it turned out, the event was “a nice meeting of the worlds,” Eriksen recalls. Minghella invited Eriksen and Lausevic (also a Sacred Harp enthusiast) to come to Romania, where they would be filming. As for the music, much of the soundtrack was then complete: “We actually used the recording we had made in Alabama,” explains Eriksen. As needed, Nicole and Law only dubbed their own voices over those of the Liberty Church singers. Thus the team was able to retain the simplicity of the sound: Sacred Harp music and Sacred Harp singers.

Furthermore, Minghella developed such an enthusiasm for this music that he made some changes in the screenplay to highlight it. Those who have seen the movie may recall that the Sacred Harp music is not merely emanating from the church in an exterior shot (which was how Minghella had originally scripted it). Instead, the parishioners sit in the traditional “open-square” arrangement, facing the center, and sing their hymn. Eriksen leads them, and Lausevic sings in the pew with young Luka on her lap.

When the DVD is released, viewers may see a backstory in which Ada’s father, a preacher (Donald Sutherland), teaches his new congregation how to sing from the Sacred Harp, rather than to sing their hymns by lining out (a leader sings one line at a time and the congregation repeats it). In this manner, the congregation sings a hymn, led by a younger preacher (Eriksen).

“My parents were disappointed when this ended up on the cutting room floor, but we didn’t mind,” says Eriksen cheerfully. “We were just so happy to be part of it at all. We’d never expected to be in the movie.”

While reminiscing about their Romanian stay, Eriksen laughs about the time his videocam caught a bear coming up toward the deck behind their villa and recorded Kidman and others chasing after it in a car.

But more seriously, Cold Mountain has had a huge impact on their lives. “It’s just wild,” he says in awe.

This fall and winter, he has been traveling the country for Cold Mountain-related events, and to work on an upcoming project. In a November e-mail update he wrote that he had been working in New York with Burnett on the new Coen Brothers film The Ladykillers. “This Sunday Minja, Luka, Anja, and I are all heading to L.A., where we’re performing at a big Cold Mountain gala event, which will include traditional Sacred Harp singers from Alabama, Sting, Nicole Kidman, and ourselves. Crazy stuff.”

And it doesn’t seem as though an end is in sight. Rolling Stone gave the soundtrack three stars, noting: “Cold Mountain’s salvation is the Sacred Harp Singers at Liberty Church, a shaped-note choral group that delivers its two hymns with an otherworldly intensity.”

Eriksen was pleased to see that the movie and music were well received, that his fellow singers enjoyed both, and that the film introduced Sacred Harp music to a greater portion of the population. “For many people,” he says, “it was an eye-opener.”

DEEP ROOTS IN OUR CULTURE

Professor of Music Neely Bruce remembers when he first heard a recording of Sacred Harp music. It was Alan Lomax’s Southern Journey, an all-day sing in Alabama in the 1950s.

“It was like a conversion experience. I listened to nothing else for two weeks; my family thought I had gone mad.”

At the time a professor of music in Champaign, Ill., he started to go to traditional sings in Alabama. “I was totally hooked. I started teaching this music to my students, and most really took to it—as is the case at Wesleyan.”

He has also become quite active in organizing annually The New England Sacred Harp Sing, which rotates among locations in Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Middletown, Conn. The last one was at South Congregational Church in Middletown in October, with 250 people attending.

As for his former student and now friend, Tim Eriksen, who is also a Sacred Harp singer, Bruce’s affection and admiration is clear. “Tim was a fabulous student. The most striking thing about him: He came to Wesleyan with two overriding musical interests—South Indian and Early American music of all kinds. He’s a fantastic fiddler and banjo player and lead singer in a rock band, Cordelia’s Dad. It’s very hard to describe them… Folk-death-metal? It’s not for the faint of heart.

“He’s quite striking in appearance: he has shaved his head, wears lots of jewelry. He looks like a skinhead, but his politics are nothing like that. I don’t want to blow his cover, but he has impeccable academic credentials. For his thesis, he discovered that every 20 years, more or less, since the early 1800s there has been a revival of this earlier music in New England.”

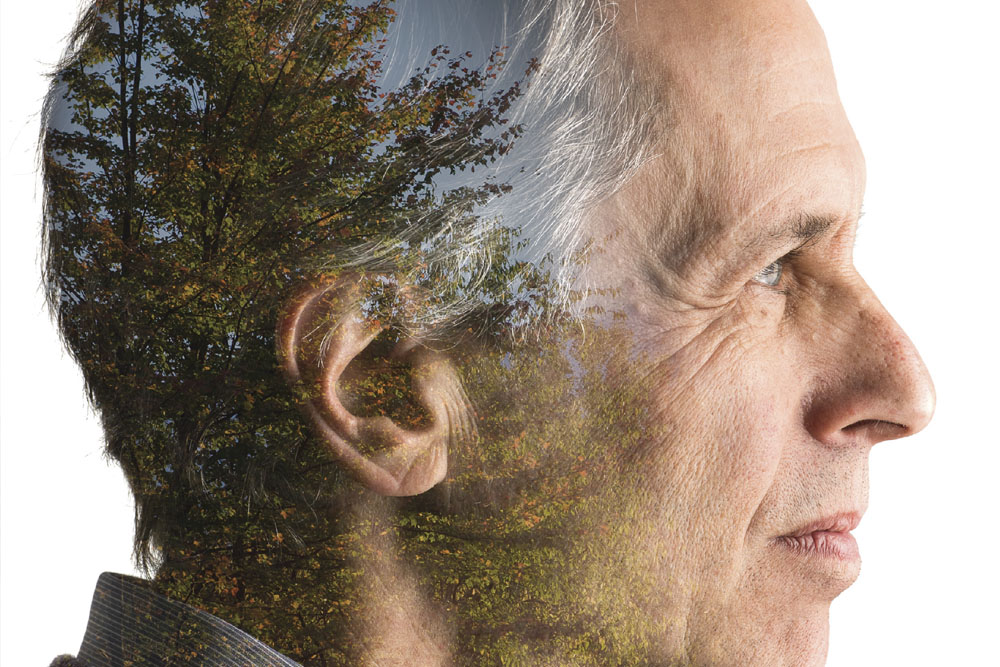

When asked about Eriksen’s work on Cold Mountain bringing this music to light, he laughs. He never thought it was particularly hidden. “It’s a curious thing,” he says, “because people do sort of know about it, but it’s in the background. It’s a music that has been part of our heritage for so long; it has such deep roots in the American culture.

“It’s like there’s a tree outside your house,” he says. “You know there’s a tree, but you don’t think about the roots and how deep they are. It’s nice to have that thought brought forth.”