THE 9/11 MEMORY KEEPER

Clifford Chanin ’75 never expected the two topics he had been working on separately for years would ever intersect. But that’s exactly what happened on September 11, 2001.

“The first thing people tell me when I tell them where I work is where they were on 9/11,” says Clifford Chanin ’75, sitting in the café of the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York, where he is vice president for education and public programs.

Like millions of people who witnessed the attack and its aftermath on September 11, 2001, Chanin has a story to share. “I was at home, listening to the radio, when the first plane struck the North Tower,” he begins. But unlike most people, who could not fathom what they had just witnessed when the second plane hit, Chanin already understood what had happened and why. “There I am sitting in the car, waiting to get across the Brooklyn Bridge, when the second plane strikes. And when the second plane strikes my first thought is, you know those people you were talking to years ago who had such deep hostility? This is how they wound up expressing it.”

A government major at Wesleyan, Chanin knew next to nothing about Islam or its radical fringe elements as an undergraduate. The step that would start him down that path came during his senior year, when he was awarded a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, a one-year grant for independent study outside the United States. His project: recording the oral histories of Holocaust concentration camp survivors who had returned to Europe. “I was interested in finding out why some survivors returned to the graveyard, as it were, when they could have gone to the U.S. or Israel or to other places around the world.”

The ambitious 21-year-old was unprepared for the emotional impact of the task he had set for himself. “This was 1975, just 30 years after the war had ended, and I was a kid driving 5,000 miles around Europe, interviewing people who had survived the Holocaust. It wasn’t until after I came back to the U.S. that I realized just how overwhelming of an experience it was.”

As overwhelming as it was, that experience sparked what became a lifelong interest in the intersection of memory and trauma.

After returning from Europe, Chanin spent close to five years in journalism and in politics, working as a reporter and serving as a spokesperson for New York City Mayors Ed Koch and David Dinkins, before joining the Rockefeller Foundation in 1990.

That year, Rockefeller Foundation President Peter C. Goldmark Jr. suggested the foundation explore what was happening in Muslim-majority countries, as he believed some aspect of the changing sense of identity in those countries would have a future impact on the foundation’s programs and on the world. Because Chanin didn’t have a well-defined role at the foundation then, he signed himself on to the project. “Islam was a very obscure subject area at that time,” says Chanin. “I remember trying to get other foundations to join, but no one was interested.”

Chanin spent the next 10 years working on the Civil Society in the Muslim World program, exploring the cultural/political turmoil in societies that had difficult economies and younger populations that weren’t being well served by educational systems. The scope of the project provided Chanin with the opportunity to engage with a wide range of people holding a wide variety of opinions and beliefs. “I met secularists, Islamic reformers, Islamists, radicals—the whole range—before any of this had been deemed significant by the world at large. For me, the opportunity was a transformative experience.”

As Chanin traveled the world, he was struck by the importance of memory in the Muslim culture, and that realization rekindled his interest in the memory issues he had explored during his earlier work with Holocaust survivors. “People in the societies I was studying would always bring up the past when talking about the present. In traveling, I began to seek out opportunities to meet people in these countries who, in one way or another, were dealing with trauma of the past. Over the course of time, meeting these diverse people in these diverse places, whether Gorée Island in Senegal, the killing fields in Cambodia, or the Gulag, I found there was an affinity among these places. Not necessarily because of the histories, which were very different, but because of the aftermath effects on a society that had been through such trauma.”

Through his years of work with the Rockefeller Foundation, an idea began to take shape: “I was trying to find the intersection of trauma response from different places that had suffered mass violence, and I began looking for grantees, thinking there had to be someone looking at this intersection already. The fact that I couldn’t find anyone was shocking to me.”

After failing to find outside grantees for such work, the Rockefeller Foundation awarded Chanin a grant to establish The Legacy Project, an organization designed to build a global exchange on the enduring consequences of historical tragedies of the 20th century. “The project really crystalized this international exchange around the issues of memory and trauma for me,” says Chanin. When he began his work on The Legacy Project in January 2000, he wasn’t sure what would happen, but he felt compelled to find out. “I said to myself, you’re going into the darkest, most obscure corner of the universe. No one will ever find you again,” remembers Chanin. “But you don’t have a lot of interesting ideas like that in your life, so I decided to see where it might lead.”

While Chanin had no idea where The Legacy Project might take him, what he never expected was for the two topics he had been working on separately for years—Muslim world development and the intersection of memory and trauma—to ever converge. But that’s exactly what happened on September 11, 2001.

“There I am trying to raise money, traveling, and doing all kinds of things, just attempting to figure out what I’m doing with The Legacy Project. And I’m sitting in the car, waiting to get across the Brooklyn Bridge, when the second plane strikes. And while I didn’t think about Bin Laden specifically, in my mind, I knew where it came from. These two discrete topics, separate and apart from one another, somehow became intermingled on that day. And it completely transformed my path.”

Almost immediately, Chanin began consulting on a variety of projects, including the startup of the 9/11 Memorial Museum in May 2005, when the foundation was first constituted. By the time the museum opened in 2014, Chanin had already curated the fifth and 10th 9/11 anniversary exhibitions, edited two books (a third is on its way), produced two original 15-minute films now shown throughout the day in the museum’s auditorium, and planned the museum’s educational programming.

“I never understood what it meant to have the life of an institution unfold before you,” says Chanin. “This museum is a living entity in the sense of the expectations and anticipation that people bring and the scale of what the place is and what the event is. We take on these active unanswered questions, whether it’s in the programs or the educational work that we do, to keep the museum a vibrant, engaging place.”

One unique challenge for the 9/11 Memorial Museum: the ongoing nature of the event. While most museums focus on preserving stories that have reached their conclusion, the 9/11 Memorial Museum encompasses the telling of an ongoing story: everything leading up to that day, everything that came after it, and every person’s story to be told. “The fact that we’re still living 9/11, part as the aftermath and part as the active threat, is a real complication in building an institution,” says Chanin. “The pieces you put on the walls of the museum are fixed—you can’t change them every week—so our educational programming and public presentations must change in order to keep the museum an animate living thing.”

Another challenge: working with constituencies that include survivors, family members, first responders, downtown workers, city residents, and others, as well as with the individuals within each constituency. “We recognized early on that with so many constituencies there would never be complete consensus on any issue,” says Chanin. “So we spent four years holding roundtable conversations with different groups in order to include everyone in the process and to make fully informed decisions about the museum. “In the end, I think our process was long enough and inclusive enough that even if people weren’t happy with the outcome on a particular point, the fact that we took the time to really listen to their concerns gave us some credibility.”

The museum and its programs are carefully designed to present the whole story without overwhelming visitors, and while respecting the privacy of the people involved. Even within the museum’s historical exhibition, where the most difficult material is found, there are alcoves—separate spaces set off from the main areas, where the material gets closer and more intimate. “Different people have different thresholds,” says Chanin. “One of the most challenging aspects of this project was recognizing how much was enough to tell the story without making it too difficult for people to deal with. We debated the question of how much is too much at many points in the process and spoke to a number of experts to make sure what we were doing wouldn’t result in re-traumatization. We always had that in mind.”

As vice president of education and public programs, Chanin, along with his team, which includes Noah Rauch ’02, director of educational programs, is responsible for the museum’s education, family, public, scholarly, and access programs, as well as for the museum’s guided tours and volunteer docents. The museum’s lesson plans and resources, created with the input of teachers and psychologists, tell the story across the curriculum. “Just like Pearl Harbor, 9/11 has become a major part of the American historical narrative, and teachers want their students to know the story,” says Chanin. “We asked the teachers what kind of materials they needed to teach about 9/11 in their classrooms, and we worked with them to develop themes and lesson plans that would fulfill their needs.” The museum also employs a staff of educators who handle school visits and camps, as well as special programs for visitors with young children. “Our age recommendation for the museum’s historical exhibition is 11 and older. But we know people come here as visitors to New York, so we’ve incorporated programs that cater to those families, using age-appropriate books and activities.”

Realizing that visitors who come to the museum with a sense of pilgrimage may also come with some degree of anxiety or fear of what they might find, Chanin’s team trains volunteers to help interpret what visitors experience in conjunction with activities and programs. The pairing allows visitors to share their own stories and cross the emotional barrier so that they can experience the museum at their own personal comfort level, something Chanin finds incredibly gratifying. “People come here with the hope, the fear, and the aspiration. They bring a lot to the visit to the museum, and being able to offer them an experience that is pitched at the right level for their expectations and anticipation is really remarkable.”

9/11: 5 OBJECTS

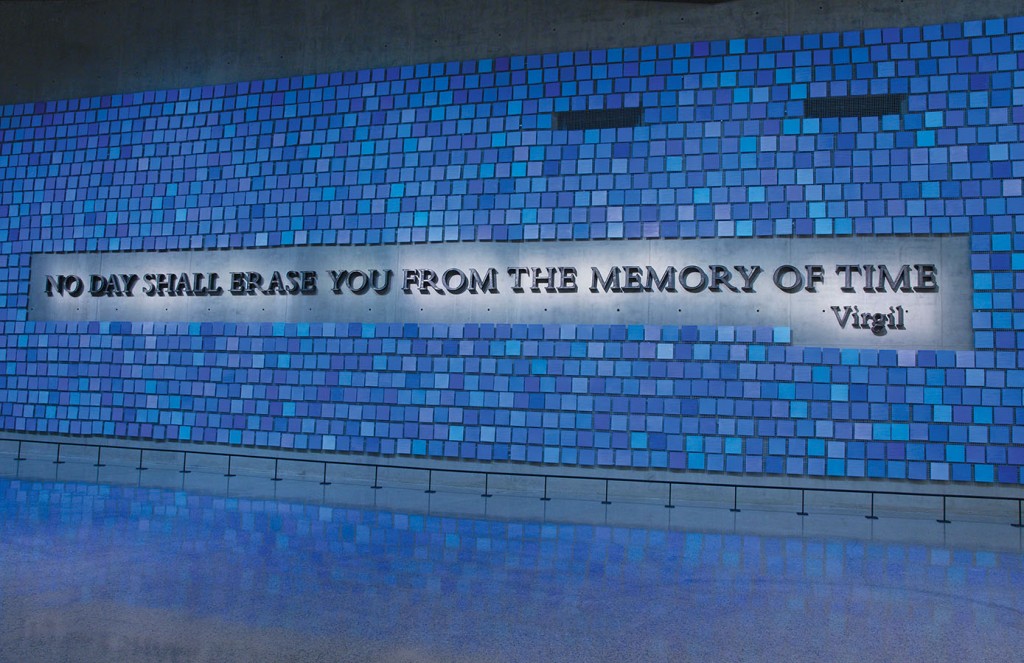

More than 4.1 million visitors from all 50 states and more than 150 countries have visited the 9/11 Memorial Museum since it opened in May 2014, cementing its status as an international place of pilgrimage. Within the museum walls are 12,500 artifacts, 23,000 still images, 1,990 oral histories, and 580 hours of video that work together to tell the story of the day, what came before, and what comes after. All personal recordings and effects were donated by and used with the permission of the families of those involved that day.

Along with the physical objects on display, the museum’s holdings include a wealth of digital and electronic material that open up the story, providing visitors with a sense of intimacy and connection. “Because I’m interested in the subject of memory and how we remember things and why it’s important for us to remember, for me the story of 9/11 is not just about the sadness of loss but also about the resilience of the human spirit,” says Chanin.