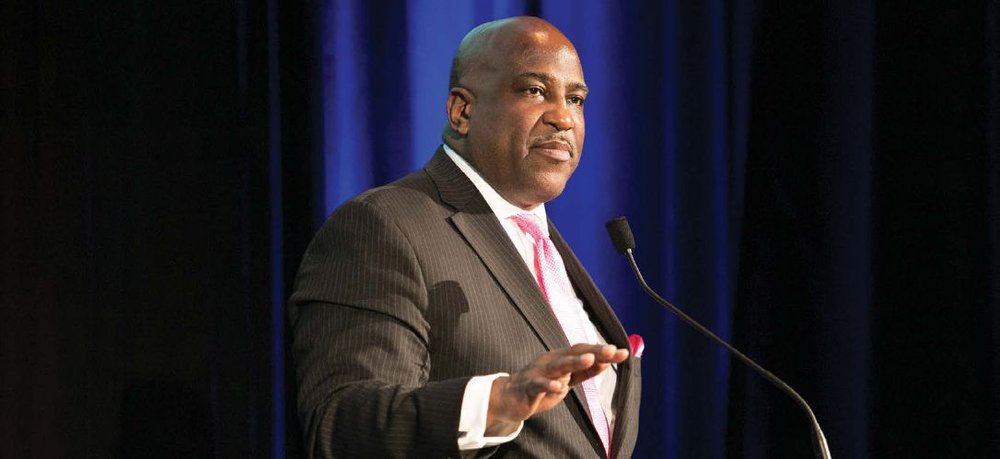

SHAWN DOVE ’84: THE MINISTRY OF REVERSING THE TREND

BY ANDREW FAUGHT

SHAWN DOVE ’84: THE MINISTRY OF REVERSING THE TREND

Twenty-one years ago, the Urban Institute think tank issued a report that highlighted 51 “promising” or “effective” programs that worked to improve the life outcomes of black men and boys, who trailed their white counterparts in categories ranging from high school graduation rates to job prospects.

A decade later, a quarter of the programs had folded, and 50 percent had stopped their efforts to help black males.

For Shawn Dove ’84, reversing the trend isn’t just a job.

“It’s my ministry,” says the CEO of the New York City-based Campaign for Black Male Achievement (CBMA), a national membership organization of nearly 5,000 multiracial leaders who come from the nonprofit, private and faith-based sectors, and academia.

Launched in 2008 by the Open Society Foundations, CBMA has since invested millions of dollars building community linkages in four areas: education, family, workforce, and a shared asset-based narrative.

“This whole notion of the American dream and the pursuit of happiness, well, there are many folks who have come to the realization that, ‘You know what? It’s not true for me,’” Dove says. “The disparities in many cases have widened.”

Dove knows those disparities: He grew up in New York (“I’ve lived in every borough except for Staten Island”), the son of a single mother who emigrated from Jamaica. While his mother worked, Dove lived during the week in Harlem with his godmother, who took in a kaleidoscopic assortment of boarders.

“While there was indeed poverty, drugs and violence, there was also a level of extended community that we don’t see today,” Dove recalls. “If I was hanging out and getting into trouble on the corner of 119th and Seventh Avenue, I’d be reprimanded by an adult who knew who I was and where I belonged.”

It was as an adolescent that Dove became interested in community organizing. He volunteered at the DOME (Developing Opportunities Through Meaningful Education) Project, which offers vocational and college counseling. With a scholarship from DOME, he attended the Lawrence Academy in Groton, Mass., where a faculty member suggested that he consider Wesleyan.

“I fell in love with the ethos and culture of Wesleyan,” he says. “There was a spirit of community, and I had the responsibility to use my talents and gifts for racial justice, social justice, and movement building.” He’d planned to become a sports writer, “but in my senior year I got scared and told myself that I wasn’t good enough. Sometimes fear makes us talk ourselves out of things.” Instead, he took work as a textile salesman in New York City. He’d find a higher calling with CBMA.

To date, CBMA has collected data and convened meetings with leaders across the country. “We’re in the midst of a fiveyear window to demonstrate that we are improving outcomes around education with a framework of High School Excellence,” Dove says. “Five years from now, if we are looking at the same data and outcomes that we see today, then we would have—to use a football term—played in the red zone but not have scored a touchdown. We’re at a pivotal moment.”

Dove’s believers are myriad, and they include Geoffrey Canada, the Bowdoineducated teacher, activist, author, and former president of the Harlem Children’s Zone, which operates three charter schools and provides poor children and families parenting workshops and preschool.

“I immediately saw in Shawn someone with extraordinary talent,” Canada says. “He reminded me a lot of myself—I mean, the Wesleyan background and coming back to your community to make a difference. He’s a great orator and he had a passion and commitment to this work that was second to none.”

Dove, in turn, credits people like Canada for advancing the conversation around racial disparities.

“I am blessed to come across, on a daily basis, resilient leaders who get out of bed every day with the hope that they can make changes,” Dove says.