NO PASSING ZONE: AMERICA’S INFRASTRUCTURE

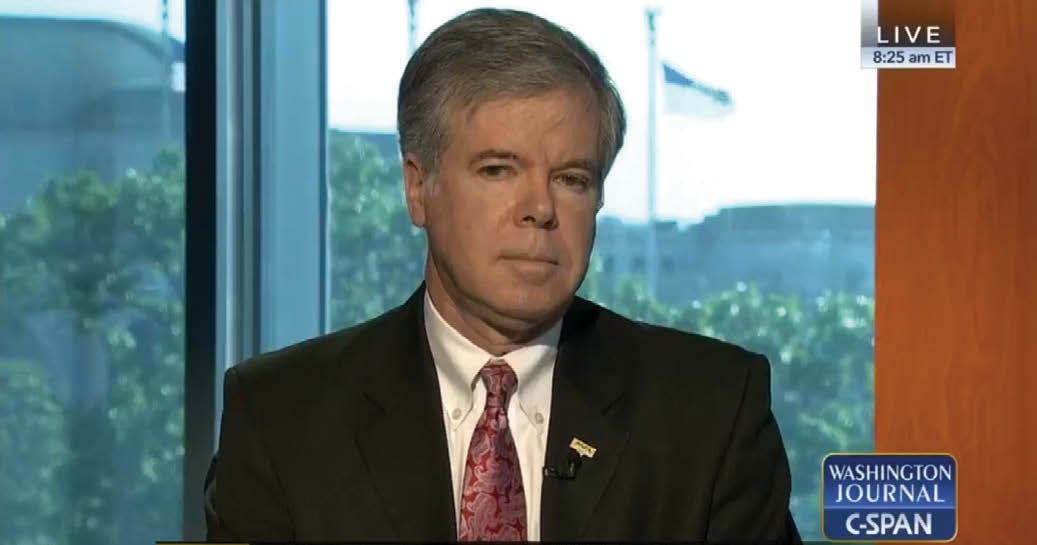

Casey Dinges ’79 and his colleagues at the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) developed a report card that has shaped the nation’s view of the dire state of our infrastructure.

Planning a trip to the nation’s capital this year? You may get a firsthand glimpse of our country’s infrastructure problems: overcrowded airports, massive traffic jams, delays on the Metro—but walking still works, if the weather cooperates.

“When I get into a car, the first thing I get is traffic information,” says Casey Dinges ’79, senior managing director at the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). “It’s an obsession here.”

Infrastructure represents more than a commuting challenge to Dinges. In 1998, he and his colleagues developed the ASCE’s much-quoted Report Card on America’s Infrastructure, which provides detailed analysis of 16 infrastructure systems ranging from aviation to wastewater. The overall grade in the six Report Cards issued since then has ranged from D to D+ this year. That dismal assessment probably comes as no surprise to air travelers or anyone trying to cope with the Washington Beltway at just about any time of day, but most Americans may be far less familiar with the nation’s inland waterways system, for example, where ships and barges displace the equivalent of 51 million truck trips per year. Its grade: D.

Presidents from Bill Clinton to Donald Trump have cited the Report Card, and it is constantly mentioned in media reports on infrastructure. More and more, infrastructure is in the news. Sometimes the reasons are spectacular, as when a massive fire caused the collapse of a portion of I-85 in Atlanta earlier this year, but Dinges points out that a water main breaks every two minutes in this country. Something bad is always happening.

The point of the Report Card is not just to raise awareness of the need for much greater investment in infrastructure, but also to prod government at all levels to take action. Dinges notes that states and localities are active, but the federal government has been “treading water,” stymied in part by toxic political discord over funding mechanisms such as raising the gas tax. The federal portion of the gas tax hasn’t increased since Clinton was president and has since lost 40 percent of its purchasing power. Meanwhile, even deeply red states such as Georgia, Indiana, Tennessee, and Utah have raised their state gas taxes (23 states in all in the past five years).

“We can’t just keep kicking this can down the road,” Dinges says. “We need for something to happen at the federal level.”

Dinges is not a civil engineer, but Wesleyan provided him with his first taste of the profession. A government major, he wrote a senior thesis, titled “The Prairie Boondoggle,” about a $1 billion project authorized by Congress in 1968 to divert water from the large Garrison Reservoir on the Missouri River in western North Dakota to the water-hungry eastern portion of the state. His thesis had all the makings of political drama: two powerful Senators from North Dakota, a heated debate between supporters and opponents, environmental impacts that included imperiling two of the largest lakes in Canada with non-native species, and a treaty violation with Canada. Dinges drove to North Dakota to see and hear about the controversy, and to Washington, D.C., where he spoke to North Dakota’s senators and to the commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation.

He could hardly have asked for a better introduction to the high stakes of massive, federally funded infrastructure projects.

“Infrastructure,” he says, “is where engineering and politics come together.”

After graduation, he got his first job with the Audubon Society in Washington, D.C. Ironically, one of his first tasks was to coordinate a grassroots and lobbying campaign to defund the Garrison Reservoir project, an effort helped by two Congressmen who, as avid duck hunters, were alarmed that the project would harm a migratory flyway. The Garrison project ultimately became a much more modest series of public works improvements.

Dinges took a position at the ASCE, the nation’s oldest engineering society, in 1986. The organization was then headquartered in New York, but Dinges joined the D.C. staff— all 2.5 of them. Ten years later, the organization moved to a sleek building in Reston, Va., a planned community in the suburban ring around Washington.

“My executive director at the time said, ‘Case, we’re in D.C. now, so put us on the map.’ He was a man of few words,” Dinges says.

A 10-year-old Reagan administration document devoted to infrastructure, “Fragile Foundations,” became the impetus for the ASCE Report Card. Congress had done nothing about “Fragile Foundations,” but Dinges and his colleagues astutely included the state of the nation’s public schools in the first Report Card, knowing that then-President Bill Clinton had a particular interest in them. Sure enough, Clinton cited the report and honed in on schools.

The Report Card has made the ASCE a go-to destination when infrastructure hits the news. The 2007 collapse of the I-35 bridge in Minneapolis, for instance, generated hundreds of media calls to the ASCE and landed Dinges on the McLaughlinGroup, a hard-hitting commentary program.

Infrastructure has long been a bipartisan national priority. President Abraham Lincoln had a vision for uniting the country by railway. Railways and inland waterways had a crucial role in the development of the country, but the national infrastructure project most familiar to everyone is the interstate highway system. First conceived by President Dwight Eisenhower as a defense-related project (he had once had the dismaying experience of trying to take a military convoy across the country), the 50,000-mile interstate highway system (combined with 100,000 miles of U.S. highways) handles 44 percent of all traffic in the United States, 75 percent of heavy truck traffic, and 80 percent of tourism traffic.

The federal government has covered most of the cost of constructing interstate highways, but maintenance falls heavily on the states, which may account for their greater willingness to raise gas taxes.

Even if Congress breaks its logjam and raises the gas tax, as the ASCE advocates, Dinges points out that growth in the use of alternative fuels means that, over time, the nation needs to look at other means of funding infrastructure. He believes that eventually we will migrate to a system based on vehicle miles traveled. Already, new methods of charging for highway use are popping up, such as differential pricing systems. In the D.C. area, for example, it’s possible to bypass miles of stalled traffic on alternate, and expensive, toll roads. It’s not difficult to foresee a not too distant future in which we pay depending upon how much we, as individuals, drive on roads—local, regional, and interstate. Dinges notes that the implications for commuting are interesting to contemplate.

Technology may also help. As future cars become equipped to communicate with roadway systems and with each other, more efficient and safer use of highways—with fewer traffic jams—will likely become possible. Self-driving cars summoned with an app and your credit card may replace the yellow cab in some areas.

“And how many cars do we need?” Dinges asks. Millennials are less eager than their predecessors to purchase a car at the first opportunity, and those who flock to cities often prefer to get a ride from Lyft or Uber rather than take on the headaches associated with car ownership in urban areas.

What’s the next project of national scope, the next interstate highway system? Dinges says he and his colleagues are asked that question all the time, but they demur. They see their role as discussing systems and needs, rather than entering the political fray associated with particular projects. When systems fail, the results can be catastrophic, as when the failure of levees in New Orleans wiped out a major portion of the city’s infrastructure—water, wastewater, bridges, roads, hospitals, schools, and just about everything else. “We put out a report calling it the worst engineering disaster in U.S. history,” he says.

Clearly, no one can predict the next infrastructure collapse of that magnitude, though the exposure of New York City to sea-level rise might be a good bet. More certain is that the demands on infrastructure will increase significantly as the population grows. Even at the current rate of one percent growth per year, the United States could add 100 million people in 30 years. This near-certainty requires long-term and strategic thinking about infrastructure and funding—an outlook that’s been in notably short supply.

Ironically, the changes needed to improve infrastructure greatly are not too large or too complex to contemplate. The United States used to spend between 6 percent and 8 percent of GDP on infrastructure improvement. That figure has declined to 2.5 percent of GDP, but Dinges says an increase to just 3.5 percent would go a long way toward addressing needs. Meanwhile, the ASCE estimates that poor infrastructure costs every family in the county $3,400 per year, or $9 dollars per day.

“That’s the drag on the economy,” he says. In spite of the nation’s dismal grade of “D+” for infrastructure, Dinges insists that he is not deterred.

“I’m getting more optimistic, because I think people are taking the problem more seriously. But then again, I didn’t think I’d be working on the Report Card project for two decades—and counting.”

DID YOU KNOW?

U.S. airports serve more than two million passengers every day. Congestion at airports is growing; it is expected that 24 of the top 30 major airports may soon experience “Thanksgiving-peak traffic volume” at least one day every week.

The United States has 614,387 bridges, almost 4 in 10 of which are 50 years or older. Just over 56,000 —or 9.1%—of the nation’s bridges were deemed structurally deficient in 2016, and on average there were 188 million trips across structurally deficient bridges each day.

The average age of the 90,580 dams in the country is 56 years. As our population grows and development continues, the overall number of high-hazard potential dams is increasing, with the number climbing to nearly 15,500 in 2016.

Drinking water is delivered via one million miles of pipes across the country. While water consumption is down, there are still an estimated 240,000 water main breaks per year in the United States, wasting over two trillion gallons of treated drinking water.

Most electric transmission and distribution lines were constructed in the 1950s and 1960s with a 50-year life expectancy, and the more than 640,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines in the lower 48 states’ power grids are at full capacity. Without greater attention to aging equipment, capacity bottlenecks, and increased demand, as well as increasing storm and climate impacts, Americans will likely experience longer and more frequent power interruptions.

The United States’ 25,000 miles of inland waterways and 239 locks form the freight network’s “water highway.” This intricate system, operated and maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), supports more than half a million jobs and delivers more than 600 million tons of cargo each year—about 14 percent of all domestic freight. Most locks and dams on the system are well beyond their 50-year design life, and delays are experienced by nearly half the vessels that pass through the system each day.

A nationwide network of 30,000 documented miles of levees protects communities, critical infrastructure, and valuable property, with levees in the USACE Levee Safety Program protecting over 300 colleges and universities, 30 professional sports venues, 100 breweries, and an estimated $1.3 trillion in property. In 2014 Congress passed the Water Resources Reform and Development Act, which expanded the levee safety program nationwide, but the program has not yet received any funding.

Today [the rail network] carries approximately one-third of U.S. exports and delivers five million tons of freight and approximately 85,000 passengers each day. U.S. rail still faces clear challenges, most notably in passenger rail, which faces the dual problems of aging infrastructure and insufficient funding.

More than two out of every five miles of America’s urban interstates are congested, and traffic delays cost the country $160 billion in wasted time and fuel in 2014. One out of every five miles of highway pavement is in poor condition, and our roads have a significant and increasing backlog of rehabilitation needs.

[Excerpted from the ASCE Report Card on America’s Infrastructure]