A Graphic Novel that Captivates

“The best graphic novels suggest rather than decree. They allow readers to search for truth in what is shown and said, but to find it in the silence between the words, the space between the images. The beguiling Queen of the Sea stands solidly among them,” writes Jennifer Donnelly in her New York Times review, “A Captivating Coming-of-Age Story Inspired by the Tudors.”

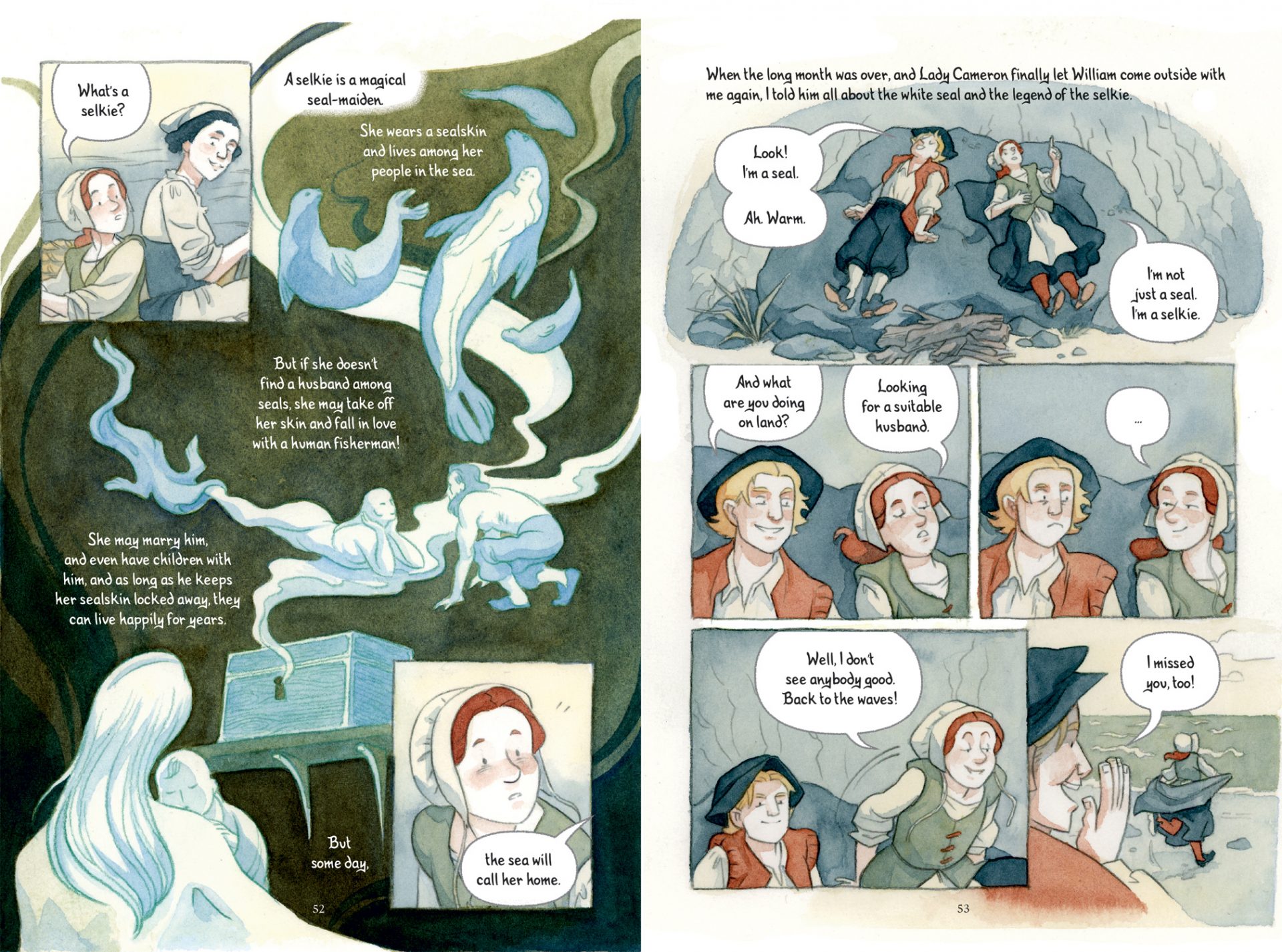

In this nearly 400-page volume, Dylan Meconis ’05 offers readers an adventure: a fictionalized version of Britain during Tudor reign, all from the point of view of 11-year-old Margaret, who has lived on “the Island” among the nuns since she was a baby. Courageous and curious, intelligent, feisty, and kind, Margaret is an appealing, trustworthy guide in this world. However, when a new young woman arrives on the island, Margaret comes to discover that much of what she believed to be true about her life is a fiction meant to protect her. She learns that her birthright offers her much larger—and more dangerous—opportunities, but only if she chooses to accept the risks and challenges of life beyond this tiny island.

Meconis’s artwork provides an immersive element to the story. Evocative, it conjures the ascetic life on this northern island with the muted natural palette of nature—olive greens, the many greys, muted reds and burnt oranges—and the characters’ clothing catches the wind from the sea and the fury of its movement in tension-driven moments. Meconis provides her characters with expressive faces—holding joy, wonder, fear and humor, determination—as these characters navigate the world in which they live, inviting us to join them there.

Below, Meconis shares an author’s note, unspooling her writing process for this novel. Spoiler alert: It traces all the way back to her childhood. She writes:

When I talk to my dad on Father’s Day, he always has the same joke for me: “You know, I always expected to be called Father. Just not by my kid.”

A good Lithuanian Catholic boy raised long before the reforms of Vatican II, my father left home to attend a conservative seminary at the tender age of fourteen. He was completely confident in his calling to the priesthood, buoyed by the examples already set by his aunt (Sr. Mary Florence, RMS) and uncle (Fr. Charles Salatka, later Archbishop Salatka of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City).

So he was indeed called Father Meconis well before he was ever a father to this Meconis. (My existence proves that there were some unexpected detours ahead.)

I grew up in the far more permissive world of the 1990s Pacific Northwest, waking up early each Sunday with my mom to attend a small, progressive Methodist church packed with openly gay members. Services there were always heavy on social justice, light on dogma. My dad stayed home, claiming to have attended enough church for one lifetime, and annoyed by the Protestant tendency to natter about bake sale committees at the expense of ritual awe. Awe, or at least silence and the lighting of more than a token couple of candles, was strictly reserved for Holy Week and Advent.

I thrived in that open community, chattiness and all, but I did come to love those special seasons of darkness best.

I was also spellbound by the contrast offered in my father’s stories of the vanished monastic world of the seminary school. The Roald Dahl-esque tales ranged from the draconic (a priest clouting him across the face with a book for the offense of smiling in the library) to the antic (midnight escapes through the steam tunnels to smuggle in precious, forbidden hamburgers) to the operatic (complex schemes to unleash justice on student bullies and faculty tyrants).

At my own school we called teachers by their first names and were firmly instructed that classrooms were a “no put-down zone.” It was a wonderful place, but short on dramatic material.

So the rosewood and silver chalice given to him at that ordination and my cartoon-covered ceramics experiments were simultaneously worlds apart, and yet shared a shelf in the family china cabinet.

There was one crucial, shared element in our formative years—the beach.

Every June, the seminary threw open its heavy, medieval doors and released its adolescent inmates into the sunshine of 1960s Southern California. My dad spent many idle afternoons bodysurfing on green waves, surrounded by bikini babes and gently stoned surfers.

And every June, my parents, our neurotic corgi, and I piled into the station wagon and drove out to a quasi-abandoned seaside township on the Washington coast peninsula. The water was considerably colder, but I learned how to bodysurf anyway, in hypothermic fifteen-minute spurts. I also spent long hours wandering the beach—collecting sand dollars, racing waves, gazing out at the surf, and pretending that I was a sea goddess or a selkie. I followed a little river back to a secret tidal island, found mysterious pathways through the woods, picked blackberries for jam. When it rained (and it usually rained), I read endless fantasy novels and drank endless cups of powdered cocoa and fiddled at endless craft projects and drew endless pictures on an endless ream of dot-matrix paper. On Sunday mornings, my dad would play a recording of the Gregorian chants he’d sung at school. The little wooden cottage would be transformed into an ancient and holy place—at least, until the album ended, and my dad switched over to Jimmy Buffett. (He insisted this was also a form of sacred music.)

The unassuming beach village had another, less obvious dimension that gradually caught our mutual attention. My dad, a history buff and researcher par excellence, began to ferret out the history of the little town and its lonely monuments. A humble cabin gift shop, well-stocked with irresistible beach kitsch, was the former hideout of a Soviet double agent who had escaped from federal lockup. The mysterious, weathered pylons that stood watch on the beach were the vestiges of a vast 19th-century resort hotel lost, twice, to fire and storm. The rocky point visible from the little river was the site where, in 1775, a crew of Spanish sailors came ashore, hammered a cross into the sand to claim it for Spain, and promptly fell into battle with warriors of the Quinault tribe who had called the coastline home for the better part of ten thousand years.

His findings gradually bent my attention from the joys of high fantasy to the boggling and heart-breaking magic of history. The cool detachment of Large Events In Distant Places was slowly replaced by a fascination with the daily lives of the people, now lost to time, who shared a geography with me; or a language, a ritual, a favorite food, a physical sensation. The whole world was overlaid with lost stories, and ghosts were paradoxically much easier for me to understand than my classmates. Traveling to a new place in the present – a hard sell for a homebody kid prone to motion sickness – also became a chance to travel to its past.

These days, my dad attends church with my mom, chattiness and all, and I go to a church in my own neighborhood, 300 miles and one major city away. Every few months we meet up at the little cottage in the little town on the edge of the Pacific. My dad has the Gregorian chants downloaded on his iPad. He brings a history book, and I bring my watercolors.

Most people ask me how on earth I came up with a middle-grade hybrid graphic novel about an only child growing up in an isolated island convent in an alternate version of the 16th century.

My father thinks it’s pretty obvious.

—Dylan Meconis ’05