Made New by the Moon: A Child’s Name

By Ian Boyden ’95

In 1996, I traveled the length of the Yangtze River, starting at the mouth and working my way up—from Shanghai to increasingly remote territory at the edge of the Tibetan plateau in Sichuan Province. Near the end, in Yingxiu, Wenchuan county, I traveled past even the edge of the languages I knew. In that town of only a few thousand people—a place I was just passing through—I heard mostly Qiang or Tibetan. I listened to a water ouzel sing on the river bank. I saw a huge silver tree. My cab driver introduced me to his wife. I didn’t know to look at every person, every house, each brick.

Twelve years later, Yingxiu was the epicenter of the 8.0-magnitude Wenchuan earthquake. Roughly 80 percent of the town was destroyed. The entire length of the Longmenshan Fault suffered untold devastation. In the wake of the earthquake, this place I’d barely paid attention to became my anchor for a project that changed my relationship to Chinese language and revealed a new form of translation through poetry.

A disproportionate number of schoolchildren in the region were killed when their schools collapsed on them. The schools were government-built, shoddily, with whatever money was left after corruption whittled away at the funds. To conceal the corruption, the government forbade parents and citizens from finding out who died and why—often using brutal tactics. Despite this, artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei created a team called Citizens’ Investigation. The team gathered and published the names of the children. In total, this list includes 5,196 names, as well as each individual’s age, gender, date of birth, and school.

Between 2016 and 2017, I pored over this list. Each morning, I read the names of the children whose birthday it was on that day. Selecting one, I then diagrammed the etymology and rebus-like structure of the characters and used that etymology as a point of poetic departure. The challenge was not to just translate the names but to give them an enduring language both to mark the loss and to insist on having the children be recognized. At the end of the year, I had written 366 name-poems, revealing a vast landscape of our humanity and our empathy. One-hundred and eight of those poems became the poetry collection A Forest of Names, which was published in 2020 by Wesleyan University Press.

Through these names I gradually began to understand language as a sensory organ that allows us to perceive elements of our world. Every language teaches us to see the world in a particular way. Speakers of Chinese and English perceive the world differently because of the languages they speak. This is why translation can be a radical act: It can introduce not just an idea from one language to another, but actually change perceptual capacities of another language.

The list of names is harrowing and exquisite—beautiful and intricate, the names are no longer carried by their children. One in particular, Made New by the Moon, holds a special spot in my heart. Made New by the Moon was born May 21, 1996. She was 12 when she died, a fifth-grader. But what makes her stick in my mind is that she was from Yingxiu, the town I’d passed through 12 years prior. Her mom would have been pregnant with her when I was there. We were in such close proximity; maybe I’d passed her in the street. Sometimes what appears to be coincidental at great distance reveals itself to be something else, a recognition of interdependency, perhaps even a mysterious seed of empathy.

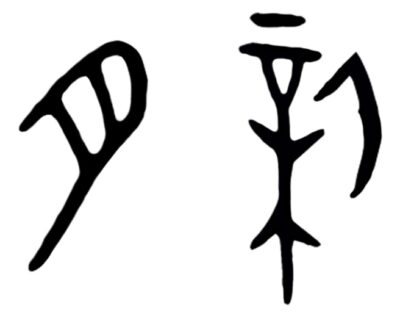

The name “Made New by the Moon” is composed of two characters, which I present here in their earliest forms, as inscribed on what are known as oracle bones (dating to roughly 3,000 years ago). The first character is 月, pronounced yuè, and it means moon. It’s an ancient character, a pictogram of the moon itself. The second character is 新, pronounced xīn, and it means new, or to make new. It is what is known as a phono-semantic compound, and is an image of a chisel and an axe. Some speculate the character contains a hazelnut tree as well. The thought is that tools for cutting trees and carving wood were an image of making something new.

Once I had those image-structures, I sat in meditation. As I thought about the child’s name, I recalled the walk I’d taken that night through Yingxiu, when I saw an oak tree, silvered with the light of an almost-full moon casting a shadow down the length of the street. Her name had opened a door in the vault of my memory:

月新

Made New by the Moon

She came with her chisels and carved,

month after month, until the tree

was a thousand feet of moonlight.

Ian Boyden ’95 is an author, curator, translator, and poet. At Wesleyan, he was introduced to Chinese paleography by studying with Phillip Wagoner, who was the curator at the Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies. He recently co-curated (with Associate Professor of Religion Andrew Quintman), the exhibition Flames of My Homeland: The Cultural Revolution and Modern Tibet, which was on view at the Zilkha Gallery from February 23 to April 1, 2021.