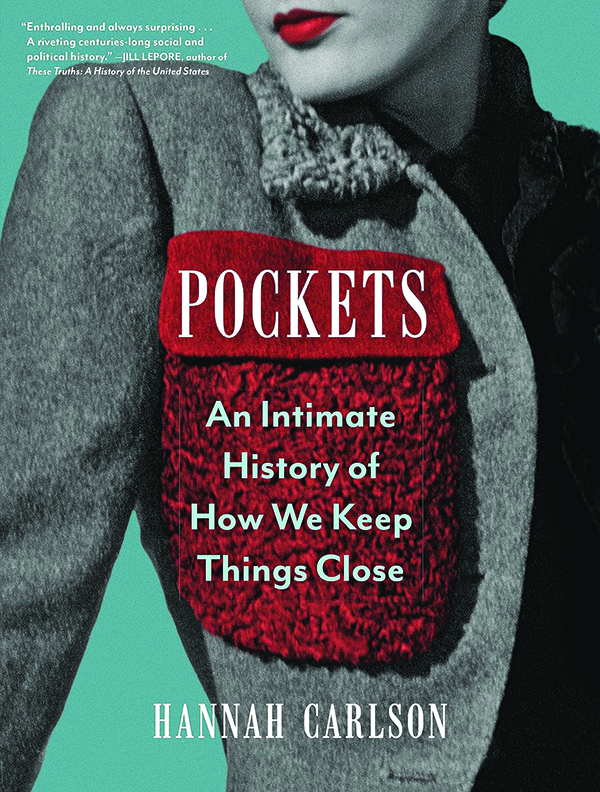

Pockets: A Review

Pockets have been on the mind of Hannah Carlson ’90 for some time. She even wrote her PhD dissertation on them. “From a material culture standpoint, clothing is one of the most intimate artifacts that we have, and for 500 years pockets have been along for the ride,” Carlson said. “The pocket turns out to be this novel way to investigate how we negotiate the world.”

In Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close (Algonquin, 2023), Carlson explores the cultural significance of pockets—hidden fabric bags that often serve as extensions of ourselves. Stitched together with 130 images and illustrations, Carlson’s book is approachable and entertaining, a comprehensive microhistory that investigates the origins of pockets from their first appearances on tailors’ receipts in the 16th century, to today’s discourse on the disparity of pockets between the genders.

If you judge this book by its cover, readers might expect Pockets to focus on the historical lack of pockets in women’s fashion—there is a chapter dedicated to it—but the history of pockets is much more complex. “It’s not just recent social media agitation for feminist pockets,” Carlson said. “This conversation has been going on for 200 years. Women’s pockets and women’s enfranchisement are often mentioned in the same breath.” She refers to an essay published by author and suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton about an argument she had with her dressmaker in 1899: Cady Stanton wanted pockets in her skirts to hold her speech notes; her dressmaker didn’t want to ruin the lines of the dress. This tension between form and function in fashion continues today.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted pockets in her skirts to hold her speech notes; her dressmaker didn’t want to ruin the lines of the dress.

Carlson credits two fellow Wesleyan alumni, Piers Gelly ’13 and Avery Trufelman ’13, for encouraging her to return to the subject after she developed academic expertise in the history and theory of art and design. In 2018, Carlson appeared on Trufelman’s Articles of Interest podcast to discuss pockets in the context of fashion history; two years earlier, Gelly invited Carlson onto his Cellar Door podcast to talk about the importance of pockets to the castaways in Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. “It’s in literature that you see objects come to life,” she said, recalling a scene in Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court where the protagonist laments the lack of pockets in his suit of armor—a slapstick scene that ultimately led her to wonder who else had written about pockets.

Along with primary source documents and art, Carlson searched everything from nursery rhymes to utopian fiction looking at language and metaphors. That’s where she noticed a reoccurring theme of pockets being associated with selfhood and privacy. Sometimes, a character’s pocket acted as an extension of that person: that Caesar carries “the moon in his pocket” (according to Shakespeare) is a sign of the general’s outsize power.

The concept of pockets as an extension of self and how that affects privacy and legal jurisdiction is one of the most intriguing premises explored in the book. The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution protects citizens against unreasonable search and seizure by government officials; pockets are protected under the Fourth Amendment, as they are viewed as private spaces. But women, whose clothes offer few options for pockets, are often obligated to carry their personal belongings in a separate, accessory container like a purse.

Carlson cited the 1999 Supreme Court case Wyoming v. Houghton, where the plaintiff argued that her purse had been unlawfully searched during a traffic stop in which she was a passenger but not under suspicion. However, an opinion authored by Justice Antonin Scalia equated purses with any other container in the car, separate from her person and liable to be searched. This established a legal precedent in Wyoming, Montana, and Ohio: In these three states women’s purses do not receive the same legal protections as men’s wallets, the latter which can be carried in pockets. If Houghton had stored the contents of her purse in her pockets, the Fourth Amendment would have protected her privacy. “In a legal context, the difference between an integral pocket and a satellite purse actually has significance,” Carlson said.