Shaping the Future of Health Care: A Q&A with Paul Kusserow ’85

by Queen Muse

America’s health care system is in crisis. Despite spending nearly 18 percent of its GDP on health care, more than any other developed nation, the United States lags behind in key health outcomes, including life expectancy and chronic disease management. Patients are facing skyrocketing costs for care and an inefficient system designed for short-term acute care rather than the long-term management of chronic conditions. If nothing changes, the burden on families, employers, and the government will only increase.

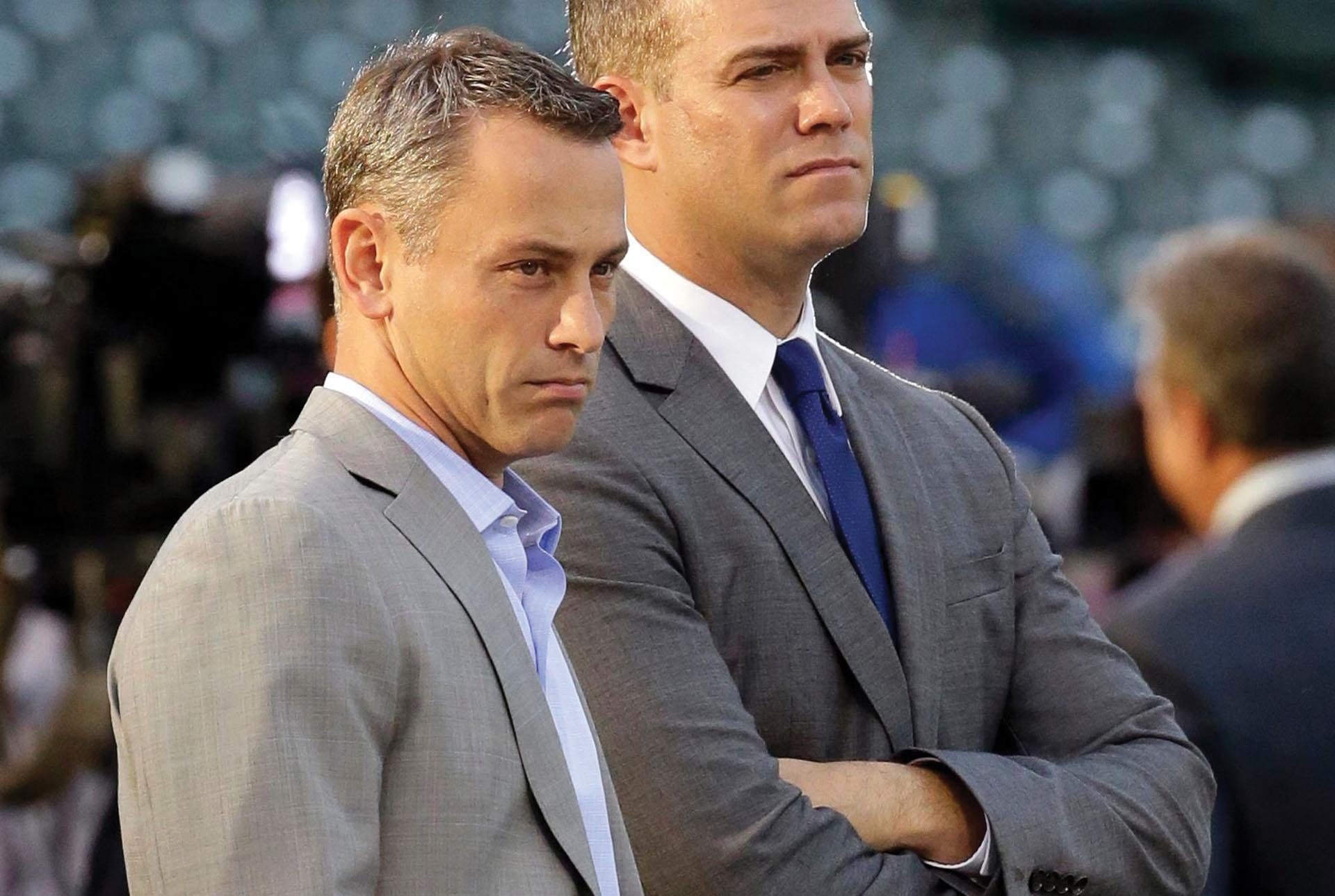

Few understand these challenges better than Paul Kusserow ’85. As the Chairman of the Board and former CEO of Amedisys, a leading provider of home health, hospice, and high-acuity care, Kusserow has spent decades at the forefront of health care innovation. A seasoned strategist with 25 years of experience, he has held executive roles at major health care companies, including Humana, Alignment Healthcare, and Tenet Healthcare. In his new book, The Coming Healthcare Revolution: 10 Forces that Will Cure America’s Health Crisis (Wiley, 2024), co-authored with David W. Johnson, Kusserow lays out a bold vision for transforming the system, one that moves away from hospital- and doctor-centric care to a model that prioritizes prevention, community-based care, and treating the “whole person.” He spoke with Wesleyan Magazine about flaws that have led to today’s health care crisis, the forces driving change, and how his experiences at Wesleyan shaped his unique approach to leadership and problem-solving.

What are the most significant flaws in the current U.S. health care system?

The biggest challenge in health care is that we’re operating in an outdated system. The U.S. health care model was designed over a century ago, between 1910 and 1920, and has changed very little despite the world evolving dramatically. Back then, people had an acute illness (one that develops suddenly and only lasts for a short period of time) and then often didn’t live past their 50s or 60s. Today, we live into our mid-80s or even 90s, but many spend 20-plus years managing chronic illnesses. Our current doctor- and hospital-centric model is unsustainable. If we continue relying on an outdated acute care system, we will bankrupt the country. Costs are rising, yet most people don’t even know what they’re paying for due to a lack of transparency.

The book outlines ten forces that might help address these flaws. Which of these forces will have the most significant impact in the coming years?

One of the biggest macro forces is demographic determinants—our population is aging, and we’re seeing higher incidences of chronic conditions. That’s putting a tremendous strain on the system. If you look at projections for health care spending, we’re on track to hit $9 trillion by 2035. We’ve already crossed $5 trillion, and at that rate, it will bankrupt the country. Our total economy is around $29 trillion, but the system will collapse if health care costs consume a third of the economy while delivering poor results. Programs like Medicare and Medicaid will either disappear or face severe cutbacks, creating a vicious cycle instead of a virtuous one. If we don’t act now, cuts will lead to worse health outcomes, especially as people age, making the problem even more severe. That said, I’m still optimistic because we’ve reached a point where we have no choice but to get creative.

You studied literature and philosophy at Wesleyan, which is atypical for someone working in the business side of this industry. How have those disciplines shaped your perspective on the ethical and philosophical aspects of health care?

I come from a nontraditional business background, having studied religion, philosophy, literature, and anthropology at Wesleyan and Oxford. These subjects may not seem directly related to health care, but they gave me a great foundation for understanding people, systems, and how ideas spread. The interdisciplinary approach at Wesleyan encouraged me to look at problems from multiple angles, which has been really valuable in my career. It also reinforced the importance of mission-driven work, which is something I’ve carried with me throughout my time in health care. I wanted to apply those humanities-based principles to an economic setting, and it worked.

How do you convince economists that caring for the “whole person” can still be profitable?

The book’s central argument is that we need to shift towards proactive, community-based care. That means preventing illness by addressing lifestyle factors, ensuring access to care, and integrating mental and physical health. By doing this, we can improve outcomes at a lower cost. Economists often come around to this perspective when they see the numbers. The reality is if you keep people healthier and out of hospitals, the system saves money. The challenge is getting policymakers and industry leaders to embrace this shift.

What impact do you hope the book will have on health care leaders and policymakers?

Policy plays an important role in shaping the future of health care. If we want to make health care more affordable and effective, we have to get away from a fee-for-service model and move toward value-based care. We also need to embrace new technologies like AI and telehealth, which can improve efficiency and access. Policymakers need to create an environment where these innovations can thrive while still protecting patient safety and quality of care. My hope is that this book sparks honest conversations about the future of health care. I want leaders to come away with a clearer sense of where the industry is heading and how to position themselves to drive change instead of just reacting to it.

It feels as if American frustrations with our health care system are at an all-time high, with the killing of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO in December and a new White House administration voicing policies that portend further disruption. How has this affected your outlook on the current health care landscape and the changes you feel are most critical?

I’m warily optimistic. From a health care standpoint, the new administration has smart and successful people who have been in the trenches and know the issues. The key is, will the entrenched bureaucrats win and outlast them as they usually do? The bureaucrats will likely do what they always do, which is cut costs by giving everything a less-than-fair inflationary increase, furthering the current system, but slowly starving it. It doesn’t solve the problem, which requires systemic structural change. It just kicks the can down the road. I’ve talked to many of the people taking leadership jobs in the current administration; they all know the list of egregious issues—pricing parity, 340-b drugs, DiSH payments, PBMs—all of which would deliver huge savings. The question is will they have the courage and political might to go after the huge, entrenched hospital, physician, insurance, and drug industry interests. Change is hard, and there will always be resistance. But I think the forces we outline in the book demonstrate that change is inevitable. The question is whether we’re going to lead that change or let it happen to us.

Are there any examples of organizations that are already embracing these changes successfully?

Absolutely. We highlight a number of case studies in the book—organizations that are using data to drive better outcomes, companies that are making health care more accessible and affordable, and systems that are successfully shifting to value-based care. These examples show that it’s possible to make meaningful improvements, even in a complex system like health care. We have the tools, the technology, and the knowledge to create a system that works better for everyone. But it’s going to take leadership, vision, and a willingness to challenge the status quo. The future of health care isn’t something that’s happening to us—it’s something we can shape.