HOOKED ON THE MUSIC OF AFRICA

In retrospect, Sean Barlow’s first visit to Wesleyan seems prophetic: it was the World Music Hall that caught his eye.

As Barlow ’79, the creator and producer of Public Radio International’s Peabody Award-winning program, Afropop Worldwide, recalls: “I looked in, and there was this… something, somehow an orchestra? With pots and pans and a gong kind of thing. Well, of course it was the gamelan. I thought, wow, this place is different!”

Enrolling in the fall of 1975, Barlow, who became a government major, says, “I fell in love with African music, studying with master drummer Abraham Adzenyah and master dancer Freeman Donkor. They really gave me the grounding of insight I stand on today.”

Banning Eyre ’79, arriving that same year, also studied World Music. His focus was Indonesian and Indian music, with T. Viswanathan and others. He majored in English and also played classical guitar. The two became friends; Wesleyan’s Winslow-Kaplan Professor of Music Mark Slobin remembers them as “the regular run of Wesleyan students—different, open, inquisitive, musical.”

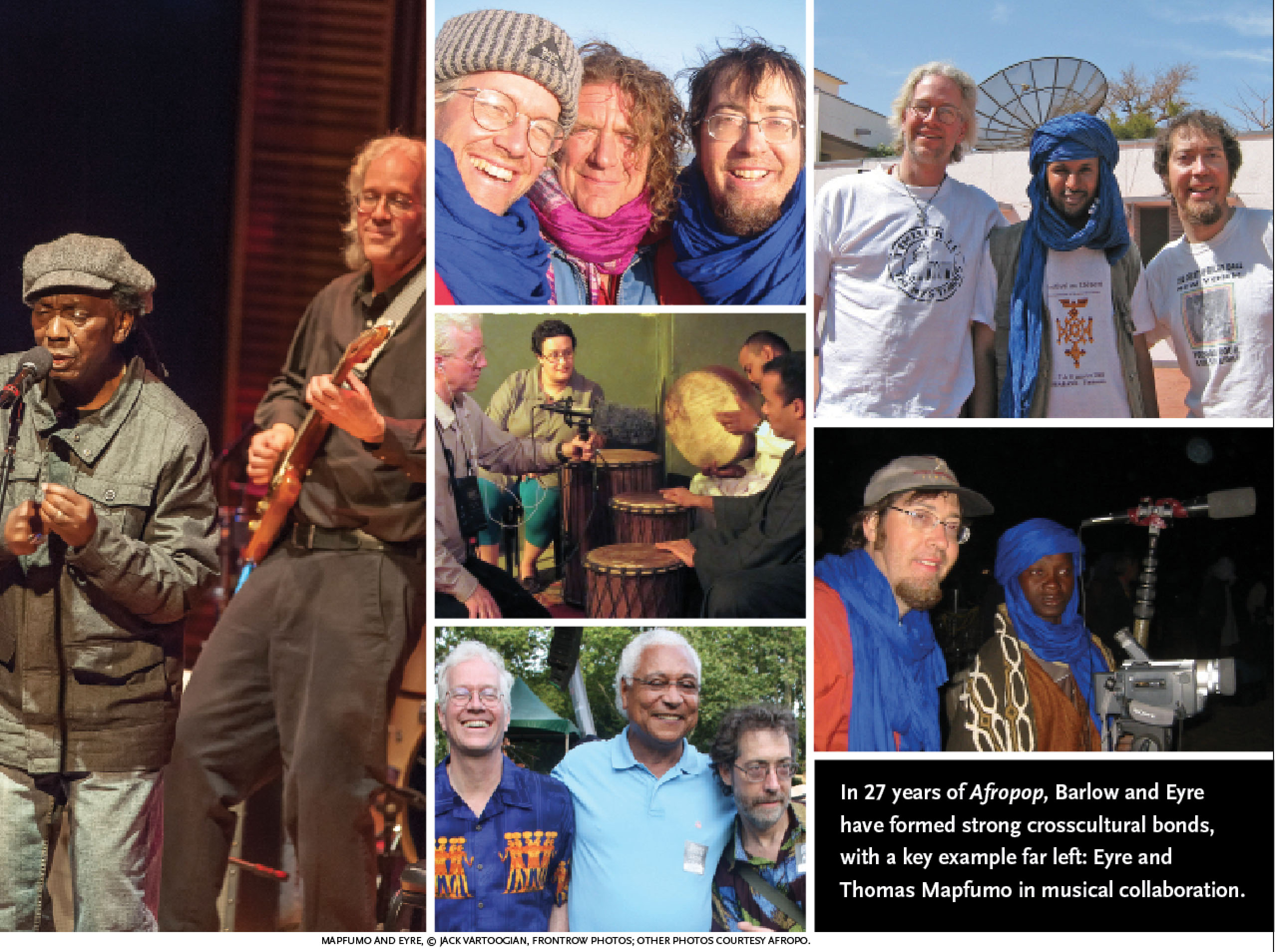

Then, from London in 1985 on the way to research the music of Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Congo, Barlow sent Eyre a cassette tape of African music, including Zimbabwean pop, with electric guitars playing the sound of the Shona mbira—an African “thumb piano.” They’d heard mbira before as undergrads, on a record from the Nonesuch Explorer series—but never before had they heard the music played on guitars. A complex musical pattern that is polyrhythmic and polyphonic, mbira music was traditionally used by the Shona people to summon ancestral spirits in religious ceremonies. The music seems to flow in an endless cascade “as if the song had been playing since the moment it was created and the player simply joined in for a time,” Eyre writes in his most recent book. Thomas Mapfumo was the artist whose band had transposed mbira music to the guitar, and Eyre was hooked—he had to learn to play that on the guitar. And he had to take a leave from his tech job to join Barlow on a trip to Africa to meet Mapfumo. That trip, which began in December 1987, was the first of many the two would take to gather stories and sounds for what was then their nascent radio show, Afropop.

As ethnomusicologists by nature (if not by degree), their fascination with Mapfumo’s music lay not only in its beauty but also in the layers beneath, threaded as it was with the culture and politics of the region. The movement to black rule in Zimbabwe was both a political and a cultural war, Eyre notes, and Mapfumo was able to use both the Shona language and the spiritual music of the native culture to stake a claim for his people.

“Politics and the modern music culture have been our entry point for so many of these stories,” explains Eyre. “In the 1980s, we were coming into these countries when they were still in the flush of this incredible excitement of achieving a new history. The immediate cultural developments that followed independence inspired us to create Afropop and drew us to places like Senegal, Mali, Congo, and Zimbabwe, where we met and hung out with musical giants like Youssou N’Dour, Ali Farka Touré, Pépé Kallé, Oliver Mutukudzi, and so many others. It was a dream come true.”

South Africa, even while still in the grip of apartheid, also offered crucial moments of a different variety. “We’d go into these huge stadium concerts—featuring stars like the Soul Brothers, Ray Phiri, Lucky Dube—where we’d be one of four or five white people,” Barlow begins.

“When they thought we were white South Africans, it was an edgier situation,” recalls Eyre. “When they found we were Americans, the whole mood would change.”

“They would all want to testify; it was really emotional: ‘You must tell your people—Apartheid is shit!’” Barlow says. “One time, by mid-concert there were about 40 people clustered around us, even standing on the roof of our rented vehicle, eager to tell their stories.

“This is our trademark: Through the magic of radio we are taking people to places where they can hear the sounds, where they can go into peoples’ homes to meet the artists in private music sessions, where the musicians and their communities can share, firsthand, stories with people around the world.” The trademark has continued for nearly three decades.

In the spring Barlow, executive producer, and Eyre, senior editor, were among the Afropop team that took the stage at a New York City gala event to receive a prestigious Peabody Institutional Award, a kind of lifetime achievement award for their entire body of work—27 years of Afropop Worldwide—a public radio production that reaches listeners on some 95 stations in the United States, with more following their podcast. Additionally, their website offers deeper explorations by scholars into the cultures, musicians, and sounds, with the Hip Deep series-within-a-series, begun in 2003 with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Among those who have added their expertise to Hip Deep scholarship are Wesleyan faculty: Adjunct Professor of Music Abraham Adzenyah, Professor of Music Eric Charry, and Professor of Religion Elizabeth McAlister.

Also in the spring, Eyre’s book, Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Music That Made Zimbabwe, was published by Duke University Press to rave reviews. The book chronicles the career—musically and politically—of arguably Zimbabwe’s most renowned musician, whom many credit as providing the inspiration for—and soundtrack to—the struggle for black rule in Zimbabwe, the former British colony of Rhodesia.

Wesleyan’s Charry, who teaches the music of Africa, as well as other areas of scholarship, such as improvisation and the music of the Americas, credits Afropop with having a major role in bringing African music to a broader American public. He frequently uses the program and website in his classes. “Some urban centers might have a random half-hour African music show, but other than that, before Afropop, there was no weekly, reliable, high-quality African music program, one that’s based on a lot of research and on-the-ground work,” he notes.

To that point, Barlow recalls a conversation with the revered Zairian (Congolese) singer/guitarist/bandleader, Franco Luambo Makiadi, in Kinshasa, back in 1985.

“I’m interviewing him—he’s a big imposing figure—and he stops me to ask: ‘We Zairians, we know Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Otis Redding. But you Americans, you don’t know our music. Why?’”

““That’s a very good question!’ I told him. ‘I’ll try to do something about that.’”

“And he’s still working on it,” adds Eyre. The two banter easily. Each adds details as the other recounts a story; they pick up different threads in each other’s narrative as they relax in the Brooklyn studio where they mix the show.

Outside, the F train rumbles by, the Gowanus Canal is a block away, and a salvage business stacks bathtubs, lamps, and wrought-iron tables behind a chain-link fence. The building that houses the sound studio is one of the anonymous, derelict-looking warehouses that line these streets. Inside, the cement stairs and halls are painted, but the paint is chipped. Behind the second-floor door that says Studio 44, however, thick and colorful rugs welcome visitors into a narrow room lined with posters, shelves stacked with CDs, and a desk by the window that holds archival equipment: a reel-to-reel tape recorder and a Technics turntable. Just to the left is the door to the state-of-the-art sound studio, where the computer and recording equipment is housed in a soundproofed room that floats on rubber cups to keep it free from vibrations from 18-wheelers on the street below and the elevated trains, says chief audio engineer and co-producer Michael Jones.

This studio is new. Prior to this, the Afropop team produced the show at Jones’ house, working around the ambient family noise and pausing their sessions to gather with the household for dinner.

The day we visit, the team is working on the weekly show, this one about the African music scene that sprung up in the San Francisco area in the late ’60s. Eyre had explored the subject in depth on a recent trip to the Bay Area. Jones and a younger engineer are mixing Eyre’s vignettes with radio host George Collinet’s narration that he’d sent from his studio in D.C., along with the music Eyre has chosen. Hugh Masekela’s number-one hit of 1968, “Grazing in the Grass,” flows out through the open door, and the mixing discussions continue around the computer inside the sound room, while Eyre and Barlow catch up with interview questions outside by the desk for a few moments.

During the near-decade between their graduation and meeting Mapfumo, Eyre and Barlow were both honing skills that Afropop would call on. Eyre had been living in Boston, studying at Berklee College of Music and writing music reviews for the now-defunct alternative newspaper The Boston Phoenix. Barlow had headed up to Alaska with a plan: work as a seasonal fisherman to fund world travel. When a community radio station opened near him in Sitka (“Raven Radio—KCAW”), seeking volunteers to keep it on air, he developed his program, Explorations in World Music. (“Pedantic title,” says Barlow; “The Wesleyan touch,” quips Eyre.)

Barlow’s first fish-funded research trip in 1984 took him to Chennai (Madras) in South India for the annual Carnatic Music Festival. (Barlow’s study of South Indian vocal music at Wesleyan inspired this project.) He returned to Alaska loaded with live recordings and interviews with master Carnatic artists, and then secured a modest grant to produce a five-part series that he independently distributed to 35 public radio stations.

When he got back from his next research trip, this one to Ghana, Cameroon, and Congo in 1985, he pitched a proposal for a 13-part Afropop series to the head of radio funding at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). However, there was pushback to his plan. The CPB executive said, “The review panel has decided that 13 is not enough; it has to make a major impact. We want 52 programs.”

“Well, I’d have to go back to Africa several times for research.”

“Okay; fine. Do you have a lawyer?”

“No.”

“Get one. Do you have an accountant?

“No.”

“Get one. Do you have a computer?”

“No.”

“Get one.”

“So all of a sudden, I was staffed up,” says Barlow. “Well, not hugely staffed, but I was equipped.”

Barlow’s second trip to Africa, this one funded by CPB, was in 1987, to Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Mali, sharing the field work with New York City composer Andrew Warshaw ’78.

Now in the thick of intensive production to make an October ’88 rollout by NPR, the next trip was in early 1988 to Zaire (Congo), South Africa, and Zimbabwe. This time he traveled with Eyre, and one key focus was finding Thomas Mapfumo.

The news they got before their flight, however, did not portend success. They had heard through connections in London that there had been “a sort of dust-up in Thomas’s band, a lot of musicians quit, and the press was saying it’s all over,” recalls Eyre. “It turned out to be just a moment, actually, but we really didn’t know what we were going to find.

“So when we first walked into the Red Lantern Inn in Harare and saw the scene and heard the band, it was like, ‘This is just unbelievable; people in the U.S. are going to love this.’”

Right after that first concert, the two put Mapfumo on the phone with Warshaw, who was working on an initiative with David R. White ’70, founder of Dance Theater Workshop and a leader in the New York arts scene. The project was to bring exceptional African artists and bandleaders for their debut tours in the United States. “We said, ‘Andrew, meet Thomas; Thomas, meet Andrew,” Barlow recalls. “And they talked—from Harare to New York—and started the process of setting Thomas on his first American tour.”

Mapfumo, Eyre notes, now lives in Eugene, Ore., having sought political asylum from Zimbabwe and Robert Mugabe’s rule, which Mapfumo had once rallied his country to support. The tale is complex, compelling, and carefully chronicled in Eyre’s book, which he has discussed in interviews on National Public Radio (NPR), Public Radio International’s The World, local stations, as well as in New York-based Zimbabwean news podcasts.

In an interview with Fungai Maboreke, a Zimbabwean with an African Internet TV outfit out of New York, Eyre explains the political climate in which Mapfumo’s music first took hold—and the importance of his use of mbira music and composing songs in the Shona language: “The nature of colonialism in Rhodesia was different from that in Ghana. Because the British wanted to live in Rhodesia, they were very concerned with manipulating the people culturally, getting inside their heads and making them ashamed of their culture. And Thomas’s messages, as much as they are political, are also cultural messages: that you have to decode, deconstruct, and deprogram that really pernicious aspect of Rhodesian rule.”

Eyre points to Mapfumo’s 1977 song, “Pamuromo Chete” (“It’s Only Talk”), as a key moment in the country’s political history. It was Mapfumo’s response to Ian Smith’s declaration that a black-ruled government would never come to their country in a thousand years. Several months after Mapfumo released this song, Smith was forced to temper that statement.

“You could hear that moral authority in [Mapfumo’s] voice in this [song],” Eyre tells NPR host Robert Siegel. “This is the moment that he’s really discovering that he can harness traditional rhythms, melody, and attitude, and make it sting.”

A decade later, however, Mapfumo found that English was most effective for his message: He wanted to broadcast to the world the moral descent within the Mugabe government. His song, “Corruption,” bore the refrain, “Something for something… nothing for nothing.”

The Mugabe regime responded to the country’s famous musician—and political activist—with increased harassment tactics, until in 2004, Mapfumo moved his family to the United States, where he lives in relative anonymity, although still performing throughout North America, in the United Kingdom, and in South Africa, and even attending book tour events with Eyre.

Eyre notes that despite the nearly three decades of friendship and the in-depth biography, Mapfumo declares that the two are from different cultures and will never reach a level of complete understanding between them—nor should they. In his interview, Maboreke questions Eyre on that point: How can a white American truly write about a black African musician?

“When you are an outsider and you are writing about a culture that’s not your own, you have certain advantages and disadvantages,” Eyre notes. “The advantage you have is that you assume you don’t know anything, so you really dig deep. … and you talk to as many people as you can. … [Y]ou know that you’re never going to be an insider. … so you work hard to get as close as you can get.”

There’s a West African proverb Eyre quotes: “No matter how long a log stays in the river, it will never be a crocodile.”

Still, there are plenty of reasons for these “logs” to be immersed in the “river” of African music, and Slobin notes that Eyre and Barlow follow flawlessly the Wesleyan tradition of ethnomusicology as demonstrated by its department’s founder, the late Professor David McAllester (with whom Barlow studied). Slobin describes the ethos with which the department began: “We have to understand the music from the point of view of those in the culture. We are not doing scientific research, we are working with people and we have to understand their aesthetics, their world view,” says Slobin. “David McAllester was the trailblazer in that sensibility of what ethnomusicology does. Sean and Banning do that. They know the musicians: they promote them; they work with them; they study from them; they have advocacy. A Wesleyan ethnomusicologist is an advocate, not a raider; a musician is not an informant but a collaborator. You enter into a long-term commitment.”

Still, there are plenty of reasons for these “logs” to be immersed in the “river” of African music, and Slobin notes that Eyre and Barlow follow flawlessly the Wesleyan tradition of ethnomusicology as demonstrated by its department’s founder, the late Professor David McAllester (with whom Barlow studied). Slobin describes the ethos with which the department began: “We have to understand the music from the point of view of those in the culture. We are not doing scientific research, we are working with people and we have to understand their aesthetics, their world view,” says Slobin. “David McAllester was the trailblazer in that sensibility of what ethnomusicology does. Sean and Banning do that. They know the musicians: they promote them; they work with them; they study from them; they have advocacy. A Wesleyan ethnomusicologist is an advocate, not a raider; a musician is not an informant but a collaborator. You enter into a long-term commitment.”

Their commitment to African music has not only deepened with Afropop, but widened over time, becoming Afropop Worldwide in the 1990s. “We realized we couldn’t just tell these stories only about the continent,” says Eyre. “There were too many connections through diaspora; it seemed arbitrary to just draw a line at Africa’s shores, so that dramatically increased the number of subjects.”

Barlow recalls the controversy that kicked up: “‘You have to keep focused on Africa,’ some people told me. But Africans travel—as do African aesthetics, instruments, spirituality, and culture. So … some of our listeners are stretched a bit when they tune in and hear Latin music—but that’s what we gave ourselves as our cultural embrace, with special emphasis on researching the musical epicenters Cuba and Brazil.”

“We want to help people understand all these cultural connections,” adds Eyre.

“Mexico, Haiti, Colombia, the Arabian Gulf cultures—all have fascinating connections to Africa that might not be immediately apparent. So that’s our mission as well,” concludes Barlow.

And Afropop continues to evolve for a new generation.

“The young African musicians’ work is infused with reggae or hip-hop sounds,” says Eyre. “The generation of musicians with whom we began Afropop are saying that the current generation has far less of an instinct to dignify and update their indigenous cultural traditions.” And, he notes wryly, the bulk of their listeners—who happen to fall into the same age demographics as Eyre and Barlow—tend to agree. “So we have a challenge to figure that out,” he admits.

Happily Wesleyan offers a solution: “This is why it’s great that we continue to bring in young interns from Wesleyan, because they have a perspective on what is current—and we have to embrace the contemporary scene—kuduro from Angola, baile funk from Brazil, Naija pop from Nigeria, reggaeton, dancehall, and, of course, hip hop from everywhere. Our Wesleyan interns have really helped us reach a younger audience, too.” [See wesleyan.edu/magazine for a story on Marlon Bishop ’07, a former intern whose Afropop work was included at the Peabody Awards gala event. Additionally, he was also honored at the Peabodys for his current work on NPR’s Latino USA.]

“The podcast is an important vehicle, too,” adds Barlow. “Not just listening to the radio on NPR at 10 on Saturday night to catch our broadcast. That’s fantastic, but a lot of people don’t do that. With a podcast, you can listen any time.”

While the two are eager to look ahead to Afropop’s future, the night at the Peabody Awards event was a time to celebrate their significant body of accomplishments. Barlow recalls the moment: “From the stage, I thanked all the artists across Africa and around the world who welcomed us into their homes, clubs and studios, sharing their music and stories. … Ultimately we take this Peabody Award as a celebration of Africa, for too long underrecognized as the deepest source of much of the world’s popular music. We want this Peabody to be an encouragement to artists in Africa and throughout the diaspora that the world recognizes their creativity, passion, and the rich cultures they embody.”

Eyre also reflected on the meaning of their work: “The message I have is what the poet Musa Zimunya says: that people undervalue the power of music in history. In Mapfumo’s biography, you can really see how a musician both affects history and reflects history—and it gives you a way of understanding a culture, politics, religion, spiritual life, social life, all these things. It’s so much more than just the story of an entertainer or of a series of popular songs. It’s all of that, but something much deeper. I hope people come away from Lion Songs, from any episode of Afropop, with a new respect for the power of music as a way of understanding the world.”

More information on Afropop Worldwide program, podcast and social media is at afropop.org.

MARLON BISHOP ’07: FROM INTERNSHIP TO PEABODY AWARD-WINNER

This year at the Peabody Awards, radio producer and journalist Marlon Bishop ’07 was called to the stage not once but twice: once for his contributions to Afropop Worldwide—which received an institutional award for their body of work—and also for his current work as producer at Latina USA, with episode #1518, “Gangs, Murder and Migration in Honduras” in 2014.

A music major at Wesleyan whose interest was in composition, Bishop says he “fully expected” to compose music for films when he graduated. However, he inadvertently set himself on another path when applied for an internship at Afropop Worldwide the summer before his senior year. Sean Barlow ’79 and Banning Eyre ’79 had been part of an open house at the Career Center, seeking an undergraduate for their weekly public radio show and accompanying “Hip Deep” series website. They needed a keen Wesleyan mind with a background in ethnomusicology. Bishop fit their criteria.

And they fit Bishop’s: “It seemed interesting, I’d had a background in World Music, and it was based in Brooklyn, near home.”

Bishop describes the experience of working in a Brooklyn storefront with Barlow, Eyre, and others as “a really fun environment—a smaller, scrappy nonprofit radio show. We were doing ethnomusicology, making accessible, grassroots documentary programming on music, history, and culture from the African Diaspora. I loved that.”

Back at Wesleyan for his senior year he was writing his honors thesis on tango music—and he kept thinking about all he’d learned with the internship. He applied for a Watson fellowship: “I proposed a project where I’d be traveling around Latin America. I’d visit six countries, spend two months in each, and document the rich variety of music made by African-descended people in Latin America.” Clearly the project had an Afropop vibe.

He received the fellowship and calls that year “the most fun thing I ever did, meeting and talking to people about music.” However, when he returned to the States in fall of 2008 right after the economic downturn, there were no jobs to be had.

That’s when he went back to Barlow. “I had all this material: I had traveled all over Latin America, visiting and interviewing musicians who had their stories told in American media. I asked if I could turn this into a radio show for Afropop.”

Barlow agreed, and Bishop produced his first Afropop show from his year as a Watson fellow in January of 2009.

“From then on, I was part of the Afropop family,” Bishop says. “Afropop was my graduate school. Sean and Banning gave me this amazing opportunity to make my own radio documentaries, and few people have that experience. I loved the process.

“I find it really satisfying to construct these stories, and Afropop has a strong following. Our listeners’ comments on our Soundcloud pages always take my breath. We are documenting audio histories of cultures that are dying as the world modernizes.

“Sean and Banning have been championing those sounds and stories for nearly three decades for the fans—and for future generations, who will want to know what the world sounded like, once upon a time. The work is invaluable.”