LETTER HOME: MAKING ART ACROSS THE GLOBE

As our van turns off the main highway, the roads become narrower, muddier, and our van swerves to avoid hitting the cows and goats pinned to the edges of the path. Farmers stop their work and boys halt their soccer game in curiosity; I know we have almost arrived. We continue and scores of children flock toward us. Some begin to jump up to peek into our van—eyes and the top of their heads popping into view for a second—while others run after us. As they run, they are framed by the mustard field landscape that extends into the horizon. When I see this vast yellow field, I know that we have reached our destination: Ishwardi, our favorite village in Bangladesh.

We have been traveling biennially to Bangladesh since 2006. After the birth of our first child in 2004, my partner, who is of Bangladeshi origin, and I vowed to nurture family bonds. So when an opportunity arose to live here for a year, we packed gladly, I leaving my position as an after-school director in New York City, she as a general counsel. We have been here since August and, more than ever, I am deeply aware of the immense beauty that is Bangladesh. While lush green pastures and rich cultural traditions have left their imprint on me, the country’s real treasures lie in the children. The Ishwardi children, in particular, have crept into my heart reminding me of the importance of worldwide community.

It was 10 a.m. and the first day of art classes at Ishwardi’s biodiversity center, UBINIG Nayakrishi Andolan, the place where we always stay. The center’s work with farmers and fishermen ensures that their livelihoods are preserved from the introduction of pesticides and GMOs. It is the children and grandchildren of these farmers and fishermen for whom I wait this morning, unsure if they really want the art I am here to share. After carefully reviewing the lesson plan, I lose myself in the adjacent pond’s calmness, holding firm to the session’s possibilities to ease my worry. I am here because of the children’s assurance last summer that they wanted more art. As anxiety sets in, I think, perhaps, they will not come and then—two by two, then three, and four—they turn the corner race-walking, then running toward our veranda. I later would learn that they had arrived early and were waiting by the entrance for a good half hour.

This day I teach them how to make rubber band bracelets. Afterward, 30 children show off the colored loops twisted around their thin wrists.

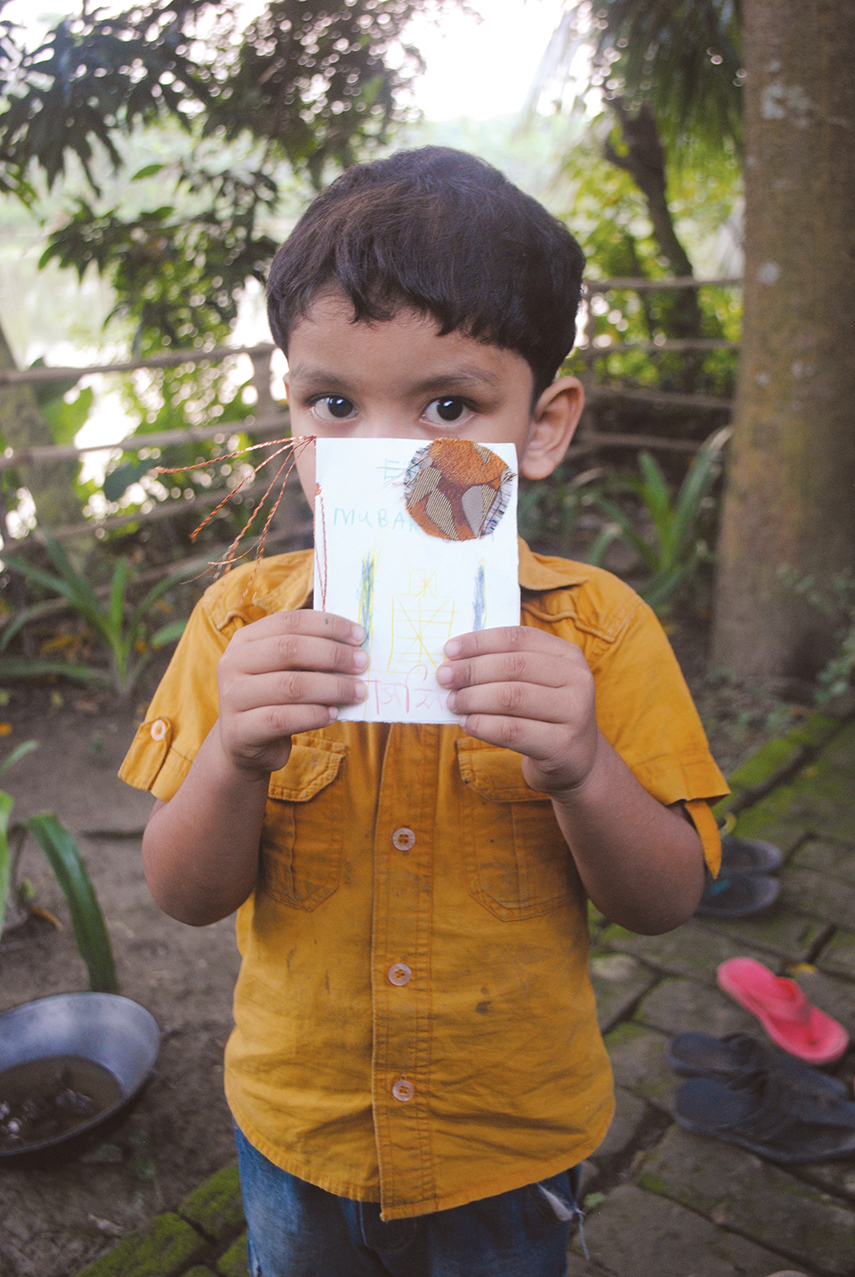

Word always spreads quickly throughout the village: Day two brings 40 children—one, even, from a neighboring village. By day six, we have 60, ranging in ages from 3 to 12. They are coming in the morning, then again in the afternoon, and then staying the entire day. We explore art and literacy, collage with cloth, meditation, and running—sprint races, which I love—coupled with dips in the pond. Although I am the teacher, they also teach me. One game, rooster fighting, has all of us “roosters” hopping on one leg, trying to topple our “rooster” friends with a gentle push and lots of laughter. Art and laughter are universal languages for children.

Just three years prior, I had founded Art in a Suitcase because I had hoped to challenge the continuous stereotypes and xenophobia that I saw, even in New York’s diverse community. Art, I’d reasoned, is a safe place to explore: There are no mistakes in art; children see one another through understanding eyes; and, most important, they instinctively want to learn something new. We would fill a suitcase full of art from a school in one country that would then make the trek to visit children in another culture who, in turn, would fill the suitcase with their art and send it back. As I have continued to build the organization, the children now ask each other questions via Twitter as a way to get to know one another.

Ishwardi has shown me that Art in a Suitcase is even more than I’d imagined, and I am continually touched by what is special about children: their fearlessness to try and their openness to difference. Even with my limited Bangla and their limited English, we have bonded. We greet each other with warm smiles, an eagerness to try a new project, and laughter. As my year abroad comes to a close, I see this as the beginning of what I hope all human interactions could be. And while the importance of family will continue to bring us back to Bangladesh, I’ll have peace of mind when I’m away. In these moments of learning together, I’ve come to believe that the Ishwardi children—and other children around the world—can steward the path for greater understanding through art. — BY MARVIN D. CABRERA ’92

Marvin D. Cabrera ’92 lives in New York City with his partner, Chaumtoli Huq, a human rights lawyer, and their two children. You can learn more about Art in a Suitcase, a global education initiative where children learn about one another through art, at artinasuitcase.org, facebook.com/ArtInASuitcase, or on Twitter @ArtInASuitcase.