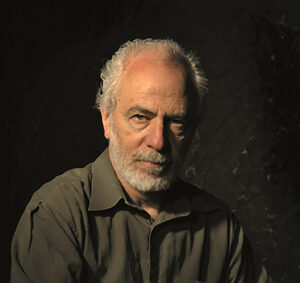

Richard Slotkin Investigates Our National Myths

Professor Emeritus of English and American Studies Richard Slotkin spent a career tracing the myths that have been with our country since its beginnings. In our fractious present, those same myths can also offer a path to a different future.

In the images of the attack on the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021, a phantasmagoria of American icons fills the frames. Rioters don cowboy hats and coonskin caps, enduring emblems of the brute force that pushed the frontier westward. They wave the “don’t tread on me” Gadsden flag, a shorthand for gun-rights absolutism rooted in the country’s origin story, and the Confederate battle flag, a signal for white supremacist violence. To Richard Slotkin, Olin Professor of English and American Studies, Emeritus, it’s as though the movement behind the attack “made powerful use of the most negative elements in the standard American mythologies and displayed them on banners.”

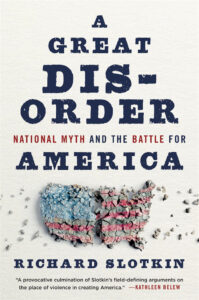

During more than 40 years at Wesleyan, Slotkin uncovered a set of foundational American myths that have echoed through the centuries. His most recent book, A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024), represents a culmination of that work, tracing how legends of the nation’s founding, its frontier, and its wars have shaped our history and contributed to our sense of what it means to be an American. In the last few decades, however, those same myths have aided and abetted a polarization that’s grown impossible to ignore on the eve of another high-anxiety election—meriting a search for new meanings within the same stories.

American contradictions have been on Slotkin’s mind since 1951, when his family drove from their home in Brooklyn, New York, to visit relatives in Miami. During a visit to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the nine-year-old Slotkin—a second-generation American for whom Abraham Lincoln was a towering figure—was bowled over by the place where the Union fought off slavery’s defenders. After his family crossed into the Jim Crow South, however, he was jarred by the park attendant who chastised him for accidentally wandering into a segregated bathroom. “This wasn’t what Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address was about,” Slotkin recalls thinking. “. . . The difference between the facts of race in America and the aspirations of American democracy: that was the problem, [and] that’s basically what I took with me through my schooling.”

In graduate school, he was struck by similarities between the 17th-century narratives of New Englanders held captive by Indigenous peoples he read in a colonial literature class and the Westerns he’d grown up watching: stories of America, framed as the experiences of white people in “Indian” country. “The cultural story was continuous,” he says. He joined Wesleyan’s faculty in 1966, established the University’s American Studies program, and refined his ideas on the myths of the American West—ultimately elucidating them in the award-winning book Regeneration Through Violence and its influential sequels—by embracing the dynamics of the classroom. “It was a constant dialogue between what I was writing and what I was teaching, where if I wasn’t sure how it’ll work—well, you have some of the smartest students in the world at Wesleyan: see what they think of it, see what questions they have about it. It was a great process for me.”

By the time he retired from Wesleyan in 2009, Slotkin’s impact was felt beyond the University. “His work, which hearkens back to the work of cultural historian Raymond Williams and others who studied myth and genre, has influenced the brilliant new scholarship on US power, culture, and politics that has come out in the last few decades,” says Jennifer Tucker, professor of history and director of the Center for the Study of Guns and Society. “. . . His important work on myths also opened up pathbreaking new insights, in particular, into the importance of symbols and narrative structures and visual storytelling.”

The myths that Slotkin identified are national myths—structures of belief that, unlike legends of up-by-the-bootstraps individualism, help entire societies craft identities. The first, the Myth of the Frontier, casts America as an expanding country, where economic and territorial growth compensates for racial violence and resource exploitation. The Myth of the Founding encapsulates the origins of the American government and its national independence. The Myth of the Civil War addresses the bloody 19th-century rupture of the country through opposing sub-myths: the Lincolnian liberation as the realization of American ideals, versus the Lost Cause, in which white supremacy is deemed worthy of restoration and defense. Finally, the Myth of the Good War venerates America as a diverse defender of freedom, embodied in what Slotkin (who, in his sprawling career, was also a novelist and film professor) calls “platoon movies,” where multiracial groups of soldiers unite to fight against totalitarian enemies.

The myths contain paradoxes and tensions—the Founding encompasses both the right to revolt and the Constitutional powers to put down insurrections, for instance—and become embedded through retelling: in political speeches and in religious sermons, in films and in school textbooks. “[A] myth isn’t just made up on the spot,” says Slotkin. “It’s a story that’s told frequently because it helps people in different situations organize their thinking about what’s happening to them.”

Over time, those stories provided scripts for action in an inexorably changing world. When the edge of the country reached the Pacific, the Myth of the Frontier justified America’s imperial adventures abroad. During Reconstruction, the Lost Cause fed the violence of Jim Crow; the solidarity implicit in Civil-War-as-liberation narratives, meanwhile, was an engine for the New Deal and Civil Rights movements. (After all, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial.) The Good War provided a pretext for American military intervention in Vietnam, while gun rights activists leaned on the Founding to push for looser firearms restrictions. “Myths are always available for reference, but myths come into play when there’s some kind of crisis in society,” Slotkin says.

Enter the 21st century, when the September 11 attacks activated the War on Terror, the 2008 financial meltdown produced the Great Recession, and ongoing culture wars collided with the election of the first Black president. “You have this decades-long crisis,” Slotkin says, “and the people who feel most threatened and imperiled by the loss of control of the government reach for myths.”

Whatever the outcome of the next election, America’s divisions have left it hurtling toward what Slotkin terms a culture war between the states.

The rise of the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement spurred Slotkin to write A Great Disorder. “It was not simply a matter of rounding out my work about American mythologies by bringing in what I’d left out,” he says. “It was doing that, and then showing how the myths that I’d been studying had become operative in the 21st century.” Against perceptions of governmental failure and social breakdown, MAGA responds by harnessing myths of the Lost Cause and the Founding. “The Lost Cause lays out a mission to restore the old order, and the revolutionary doctrine [of the Founding] gives you the means to do it: armed force.”

The opposing end of the political spectrum, Slotkin says, also draws on myths—namely, the Good War and the liberation myth of the Civil War—but without a firm shape. “The left really developed as a reform movement in part by critiquing American myths, by challenging their authority, by saying, ‘Yeah, the settlers developed the frontier, but at what cost to the environment? What was lost in the suppression and dispossession of Indigenous peoples?’” he says. “. . . It’s that critical disposition that makes it hard to fabricate a story.”

Whatever the outcome of the next election, America’s divisions have left it hurtling toward what he terms a culture war between the states, Slotkin says: “two different political orders in the boundaries of a single, supposedly unified nation-state,” each functioning differently with respect to voting rights, education, healthcare, trans rights, and so on—something like a 21st-century Jim Crow regime. Still, he maintains a glimmer of hope. “All of these things that look very dire, to me, can be checked or reversed by a strong, politically active counter movement, but such a movement has to be organized, focused, and maintained through months and years of hardship,” Slotkin says. “I don’t at all underestimate the difficulty of achieving that.”

Bringing such a vision into reality also demands different stories. As Slotkin notes, there is no modern nation-state whose history is not rife with social injustice. “What is admirable about America is not its supposed exception to these patterns of history, but the struggles of its people to amend injustice, and realize a broad and inclusive nationality.” A narrative can be made of these struggles, which would root the vision of American reformers in a new national myth—and, perhaps, deliver a new measure of equity to the story so far.